My toddler first memorized the sounds of hiragana (basic form of Japanese syllabary) by ear when she was just about to turn two, and learned to read them at three. Now almost a year later, she is practicing how to write it alongside the English alphabet. It amazes me how she can pick up something so complex. Honestly, if I weren’t Japanese I probably wouldn’t choose Japanese as a second language. Because, to use my daughter’s current favorite word, it’s “daunting.” Thai or Myanmar/Burmese script feels impossible for me to learn, and I imagine that it’s probably the way some people feel about Japanese script. Japanese written language contains a lot of shapes unfamiliar to the alphabet, and there’s also an overwhelming amount of them.

To give a little background, the first historical evidence of written Japanese language dates back to the 8th century. Hiragana and katakana developed in the following century out of a need to simplify reading the overwhelming amount of kanji, or Chinese characters, that held both phonetic and semantic value. Kanji still to this day has these values and we use about 2,000 of them on everyday conversational Japanese. One kanji can be read many different ways and hiragana helps to identify the correct reading in the way it is used. It’s a lot for even an average Japanese person to keep up, trust me.

Hiragana is used in word endings and is the first form of writing that Japanese children learn to read and write. It is also used for furigana, a writing style in which hiragana appears on top of kanji (in horizontal texts) or left of kanji (in vertical texts) to assist the reader with pronunciation of kanji. Katakana, which are pronounced exactly the same as hiragana but written differently, is used to write foreign words and for specific words like animal names. While hiragana has a round shape like cursive writing does, katakana takes more rigid and angular strokes.

Both hiragana and katakana are made up of:

- 46 basic syllables

- 25 additional ones with diacritical marks to pronounce some syllables stronger (20 dakuon, 5 handakuon)

- 33 yōon (combination of consonant with a slight ya/yu/yo sounds to pronounce intricate nuances

- 1 sokuon, a letter that has no sound, usually used between two syllables.

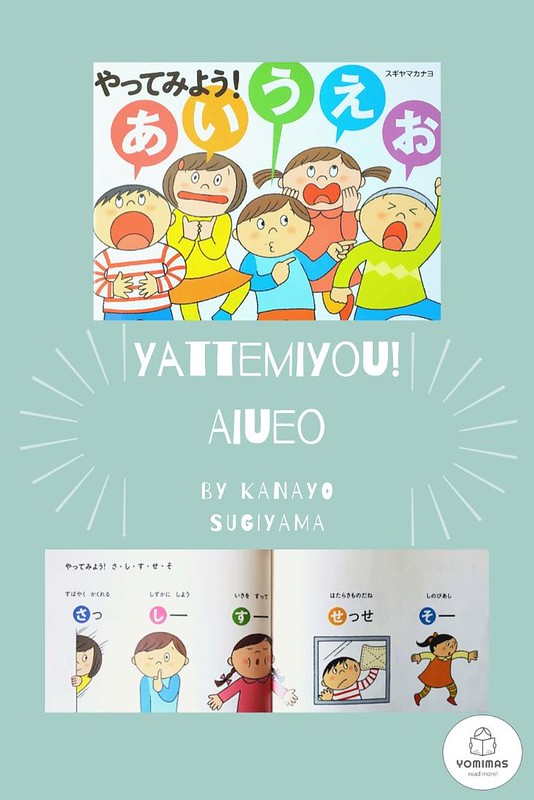

Japanese is a relatively musical language that relies heavily on onomatopoeia. There’s an onomatopoeia for just about everything, from emotional expression to how the rain falls to the ground. When a book introduces basic Japanese syllables in a musical form, you get to learn both the syllables in order and how to use it as an expression. The book that does it all is Yattemiyou! Aiueo by Kanayo Sugiyama. It’s not a storybook, but it lays out all the 46 syllables in order, in groups. Each syllable is linked to an expression, sound, or a word. The pace that the author leads you to read aloud helps anyone to memorize the syllables rhythmically and accurately. This was the book that my daughter memorized when she was just turning two, as if it were a song. Inside of the front and back covers show the syllables with diacritical marks, and these have come in handy now that she’s learning to read those sets. Learning Japanese syllabary is daunting but it doesn’t always have to be!

I purchased the book from Kinokuniya, but it is also available on Amazon.co.jp. If you or your child is a beginner Japanese student learning to read and write, you can also start with this book: Kana Can Be Easy by Kunihiko Ogawa (my husband always makes fun of this book because of my name in the title).

Lastly, here are some useful articles in familiarizing yourself with hiragana:

“Japanese Hiragana” by Omniglot (includes hiragana and katakana charts)

“An Overview and History of Japanese Language: Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana” by Hub Japan

“Hiragana Chart “ by Darthmouth University

“Japanese Onomatopoeia: The Definitive Guide” by Aya Francisco on Tofugu

やってみよう!あいうえお

スギヤマカナヨ 作

私は日本で生まれ育ち物心がついた頃から日本語を喋り、ひらがなを読んでいたので、「ひらがなを習う」という苦労を知りません。娘に初めてひらがなを教えたのは2歳になるかならないかの頃。作者スギヤマカナヨの「やってみよう!あいうえお」を図書館で借りたのがきっかけでした。まるで歌みたいにリズムがある作品なので、娘はセリフに続くひらがなの音をあっという間に覚えてしまいました。その後3歳になる手前に一字ずつしっかり覚えさせました。もうすぐ4歳になる今はひらがなを書く練習をしています。

ひらがなのことを普段ここまで考える機会はなかなかないのですが、改めてリサーチしてみると結構難しいことを子供に習わせてるんだなぁと実感しました。ひらがなを詳しく説明すると:

- 清音46文字

- 濁音20文字

- 半濁音5文字

- 拗音33文字

- 促音1文字

これだけでも105文字!なのにまだその上に漢字2000文字以上を加えるというスパルタ日本語文化。それに比べると英語のアルファベットはたったの26文字。日本人は大変な努力をしているんです。勉強が嫌になって当たり前なんです。こうやって数で比較してみると、日本語を習得している外国人の人も相当努力していることがわかります。多分私がタイ語とかミャンマー語を学ぼうと思っても全く読めないのと同じくらい皆最初は困ってるのかな、と勝手に想像しています。

「やってみよう!あいうえお」は日本語の特徴とも言えるオノマトペを最大に活かしてひらがな教育につなげています。「びっくりした あっ!」や「へーんしん!とぉー!」など普段使うような表現から絵本やアニメなので使われる表現がたくさん出てくるので、馴染みやすいです。動作で覚えることができるのですぐに実践出来る。体で覚えれるので「読む」というよりは「やる」で頭に入る。そういう点では素晴らしい本だと思います。本のカバーの中は濁音や半濁音が紹介されています。気軽にひらがなを覚えることができるこの本は育児の味方です。作者さんには是非カタカナ版もお願いしたいところです。